Introduction

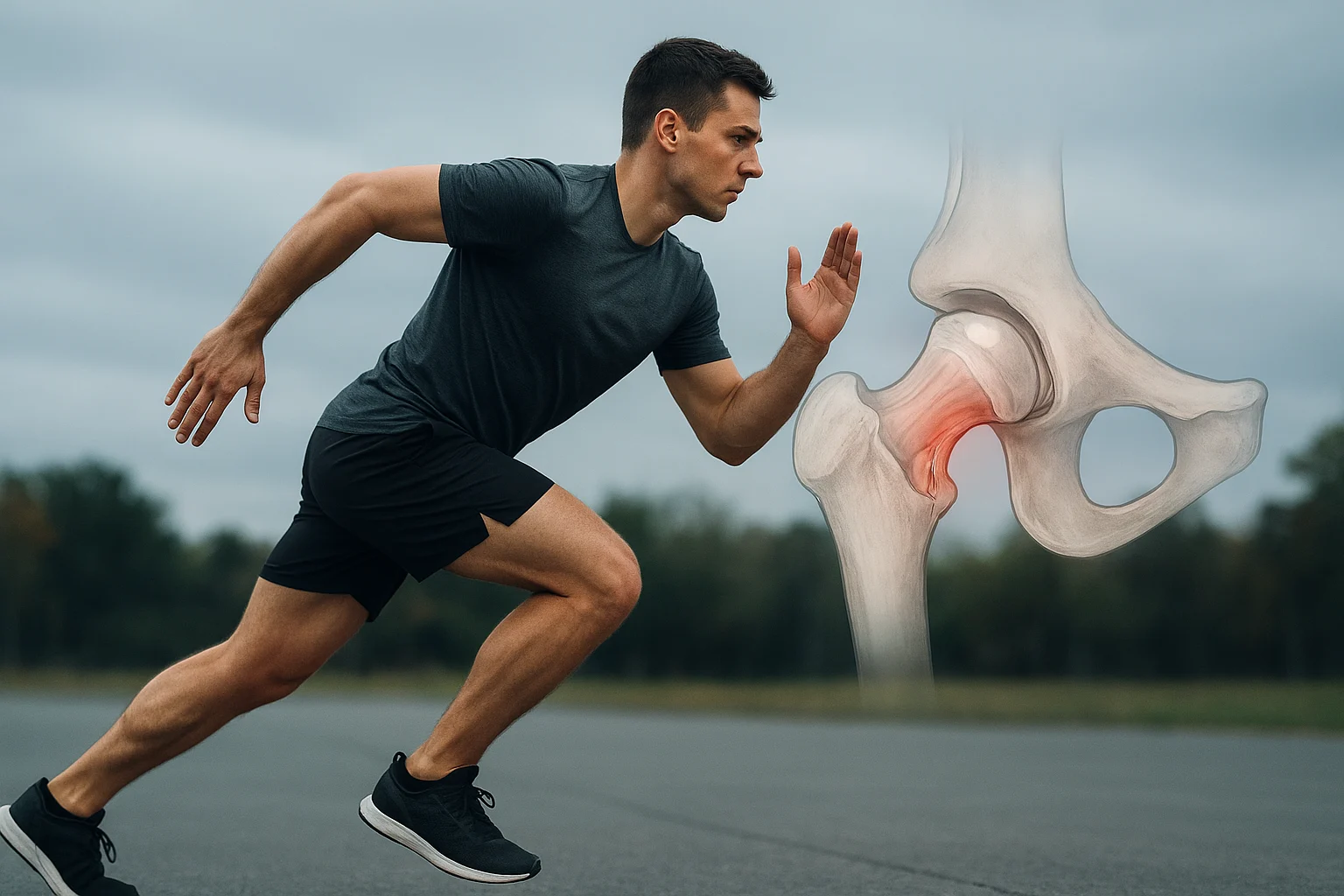

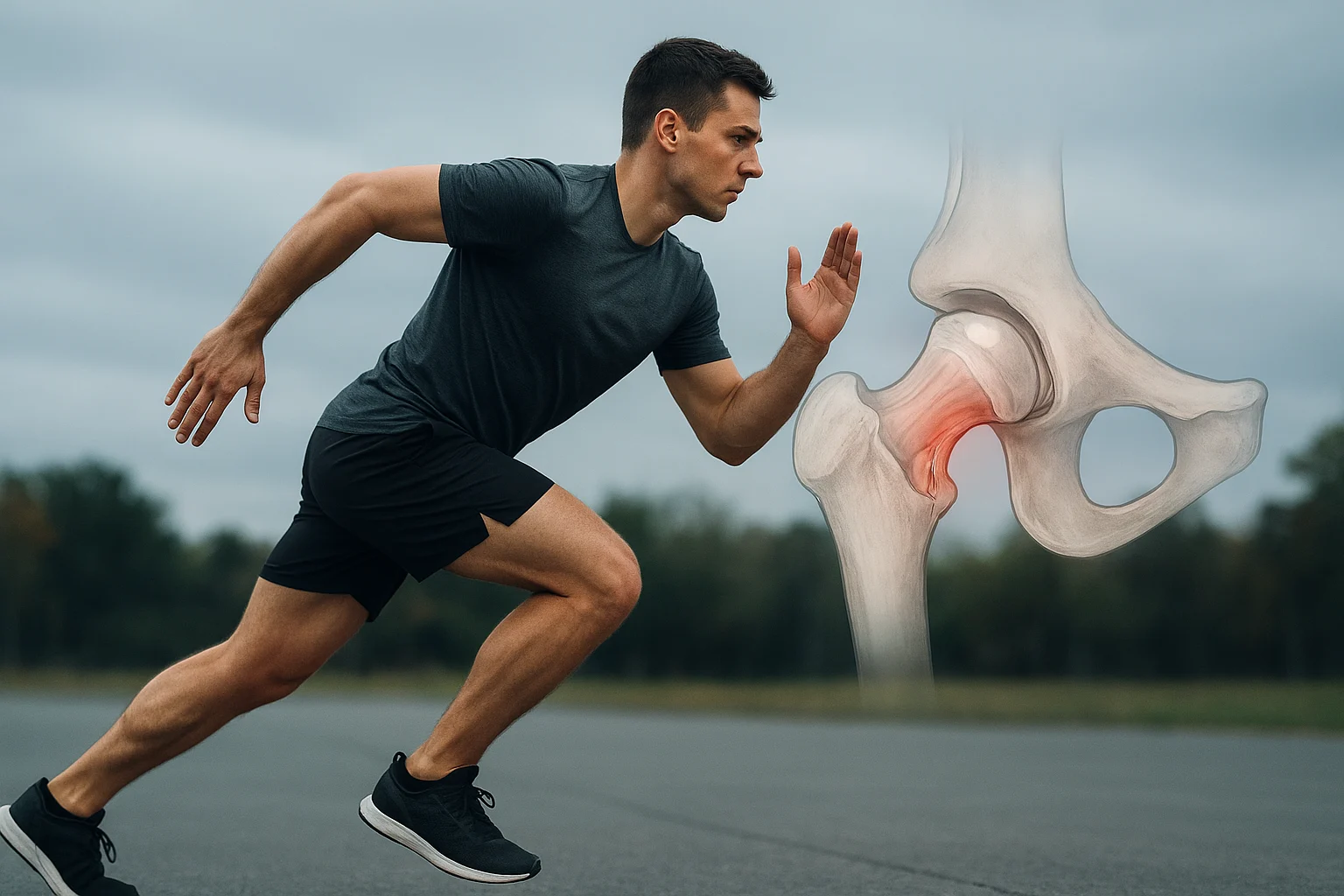

For the younger, physically active adult who plays sport, runs, or regularly trains, a tear in the hip’s labrum may seem rare — but it is far more common than many realise. The Acetabular labrum (the cartilage “ring” around the hip socket) serves important roles in stability, shock absorption and joint lubrication. When it’s damaged, it can lead to persistent groin pain, reduced movement, a sense of catching or clicking — and frustration when the athlete is eager to return to full performance.

While labral tears have traditionally been associated with older or degenerative hips, they are increasingly being recognised in younger, “active adult” populations — particularly where underlying hip morphology (such as Femoroacetabular impingement / FAI) exists, or repetitive loading and twisting movements occur.

In this article we’ll look at:

- Why labral tears happen in active adults

- Diagnostic pitfalls and what to watch out for

- Treatment options (non-surgical and surgical)

- Rehabilitation and the return-to-sport timeline

- Key take-home points, and a handy FAQ at the end

Why Labral Tears Occur in Active Adults

Underlying anatomy + repeated loading

The labrum is a fibro-cartilaginous rim that deepens the hip socket and helps seal the joint. Tears often occur because of abnormal joint mechanics rather than purely traumatic events. Common contributing factors include:

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) — where the femoral head/neck and acetabulum conflict in certain movements.

- Hip dysplasia or subtle bony abnormalities that increase edge-loading of the labrum.

- Repetitive high-velocity or high-twist sports (soccer, hockey, long-distance running, pivoting) that subject the hip to microtrauma over time.

- Capsular laxity/hypermobility, or previous hip injury.

Why the “younger, active” cohort?

Active adults who push their hips through extremes of motion or high volume of repetitions are more vulnerable. Contrast this to older adults whose labral tears may be more degenerative in nature. The active adult is often trying to train, play sport, perform functions — and a labral tear may derange that.

Why the consequence is significant

A torn labrum may destabilise the hip joint, allow abnormal cartilage loading, and, if left unmanaged, contribute to early osteoarthritis. For an athlete or highly active adult, it can mean loss of training time, sub-optimal mechanics, compensatory injuries (in knee, back, SI joint) and delayed return to full performance.

Diagnosis: Pitfalls & Best Practices

Typical symptoms

In an active adult you might expect:

- Deep groin or front-hip pain (especially with hip flexion, rotation)

- A clicking, catching or “locking” sensation in the hip during certain movements.

- Stiffness or deterioration in performance during sport/training (reduced kick-back, cut movement pain)

- Pain prolonged by sitting, entering or exiting car, squatting.

Diagnostic pitfalls

- Mistaking the symptoms for other causes: e.g., hip flexor tendinopathy, glute med overuse, SI-joint dysfunction, back referral or adductor strain. Careful history and exam are needed.

- Imaging false-negatives: Standard MRI may miss labral tears; the gold-standard imaging in many cases is MR-arthrography (MRA) or MRI with contrast/injection.

- Focusing only on the labrum: Often there are concomitant issues (e.g., FAI bumps, cartilage damage) which need to be addressed for full resolution.

- Over-looking motion/biomechanics assessment: For the active athlete, examining hip strength, control, glute and core activation, movement patterns is critical (not just imaging).

Diagnostic approach – key steps

- Clinical history: onset, aggravating activities, sport-specific movements, effect on training/sport.

- Physical exam: special tests (e.g., combined flexion-adduction-internal-rotation (FADIR) provoking hip pain) may suggest labral involvement.

- Imaging: start with X-rays (check for bony morphology, dysplasia, FAI). Then MRI/MRA for labral and soft-tissue evaluation.

- Diagnostic injection: In some cases, an intra-articular local anaesthetic injection can help confirm the joint as the pain source.

Treatment Options

Conservative / non-surgical first

In many active adults, early treatment aims to relieve symptoms and restore function before considering surgery:

- Activity modification: avoid positions/movements that provoke symptoms (deep flexion, internal rotation, pivoting).

- NSAIDs / pain relief as required.

- Physical therapy: A structured programme aimed at restoring hip/core strength, improving movement mechanics, correcting muscle imbalances, and gradually returning to sport-specific loads.

- Intra-articular injections: In selected cases (corticosteroid or other) to reduce inflammation/pain and help diagnostic clarity.

Effectiveness: While conservative management is a reasonable first step, persistent symptoms, mechanical catching/locking or underlying bony impingement often lead to surgical referral.

Surgical intervention

Indications for surgery include:

- Persistent pain/functional limitation despite 3-6 months of appropriate conservative care

- Mechanical symptoms (catching/locking)

- Underlying bony abnormalities amenable to correction (e.g., FAI)

- In high-level athletes aiming to return to pre-injury performance

Surgical options typically include arthroscopic repair of the torn labrum (preferred over debridement when possible), sometimes combined with correction of bony morphology (e.g., cam/pincer lesions).

Post-surgical rehab is critical (see next section). Recovery timelines typically range 3-6 months minimum to return to sport in many cases.

Rehabilitation & Return to Sport

Rehab is arguably where the success of the active adult’s recovery lies. Whether following conservative care or post-surgery, the principles remain similar — just the timeline and restrictions differ.

Key Rehabilitation Phases

- Initial protection / symptom control

- Pain/inflammation reduction

- Gentle range-of-motion work (avoiding provocative positions, e.g., extreme flexion/internal rotation)

- Controlled weight bearing (especially post-surgery: protocols may restrict weight bearing for several weeks)

- Strengthening & movement re-education

- Focus on hip abductors/glutes, core stability, external rotators; correct faulty movement patterns (such as excessive hip adduction, internal rotation)

- Introduce closed-chain and sport-specific drills, dynamic control, proprioception exercises.

- Sport-specific loading & return to full activity

- Gradual progression to higher-speed, multi-directional movements, cutting/pivoting as tolerated

- Monitor for symptoms — pain or catching should prompt modification

- Athletes typically return to full sport 3-6 months (or longer depending on complexity) post-surgery.

Specific Considerations for Active Adults

- Emphasise correcting any asymmetry or imbalance that may have contributed to injury (e.g., hip flexor dominance, glute med weakness).

- Movement quality matters: assess technique in sport/training (e.g., how the hip moves in squatting, lunging, cutting).

- Gradual return—avoid “jumping in” at full intensity too early, as this may risk re-injury or persistent hip issues.

- Monitor fatigue and training load: even after return to sport, ongoing strengthening and conditioning is important for long-term hip joint health.

Return to Sport Checklist

Before full return, consider whether the athlete can:

- Perform sport-specific drills at full speed without pain or catching

- Demonstrate symmetrical strength and hip control (especially abductors, external rotators)

- Move through full hip range of motion comfortably, including those positions that provoked symptoms pre-injury

- End session without new groin/hip pain or “giving way” sensation

- Maintain training load, including warming up and cooling down, without flare-up of symptoms

- If these are met, it is reasonable to progress to full participation under guidance.

Key Take-Home Points

- Hip labral tears should be on the differential in younger active adults presenting with groin/hip pain, especially in sports with high hip demands.

- Diagnosis can be tricky — physical exam + careful history + appropriate imaging (often MRA) are needed to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis.

- Non-surgical treatment (activity modification, therapy, strength/conditioning) is appropriate first line; however, some cases will require arthroscopic repair to restore full function.

- Rehabilitation is central: successful return to sport depends on strength, control, movement quality and gradual increase in load.

- Even after return to sport, ongoing hip health (load management, conditioning, correction of biomechanical faults) is crucial to prevent recurrence or progression to hip joint degeneration.

FAQ

Q1: Can a hip labral tear heal on its own?

In many cases, a labral tear will not “fully heal” on its own and resolution of symptoms may rely on conservative management (therapy, load modification) or surgical repair. However, with mild tears and appropriate management, function off the tear may be achieved.

Q2: How long until I can return to sport?

It depends on the severity of the tear, whether surgery is required, the athlete’s baseline, and sport demands. For surgical repair, many athletes return to full sport between 3-6 months; some may take longer. For non-surgical cases, timeline is more variable and depends on symptom resolution and functional progression.

Q3: What are the signs that someone may need surgery rather than continue with conservative care?

Signs include: persistent mechanical symptoms (catching/locking), ongoing hip/groin pain despite ≥3-6 months of appropriate conservative treatment, underlying bony morphology (e.g., FAI) likely to interfere with joint function, or high-level athlete intent on full return to performance.

Q4: What is the most important part of rehab?

Key components: restoring hip and core strength (especially glute med/abductors), correcting movement patterns/biomechanics, gradually loading the hip in sport-specific ways, and ensuring pain-free progression. Without good rehab, return to sport risks being compromised.

Q5: How can I reduce the risk of labral tear recurrence or further hip damage?

- Consistent hip and core conditioning (not just during rehab but ongoing)

- Warm-up and mobility work before sport/training

- Avoiding excessive deep hip flexion, internal rotation, or pivoting without control (especially when fatigued)

- Addressing and correcting muscle imbalances or previous injuries that may alter hip loading

- Monitoring training load/fatigue — ensure gradual progression and adequate recovery