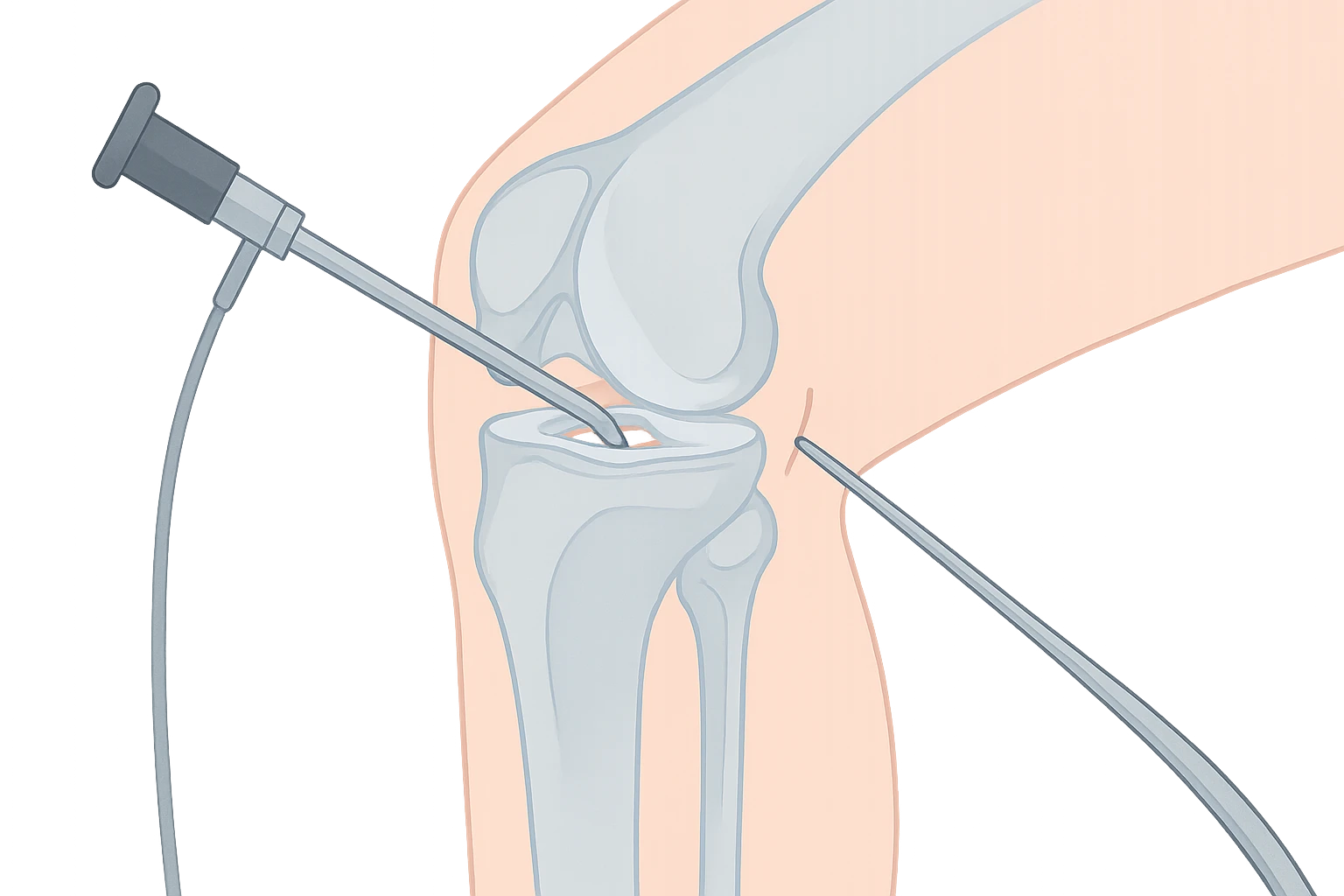

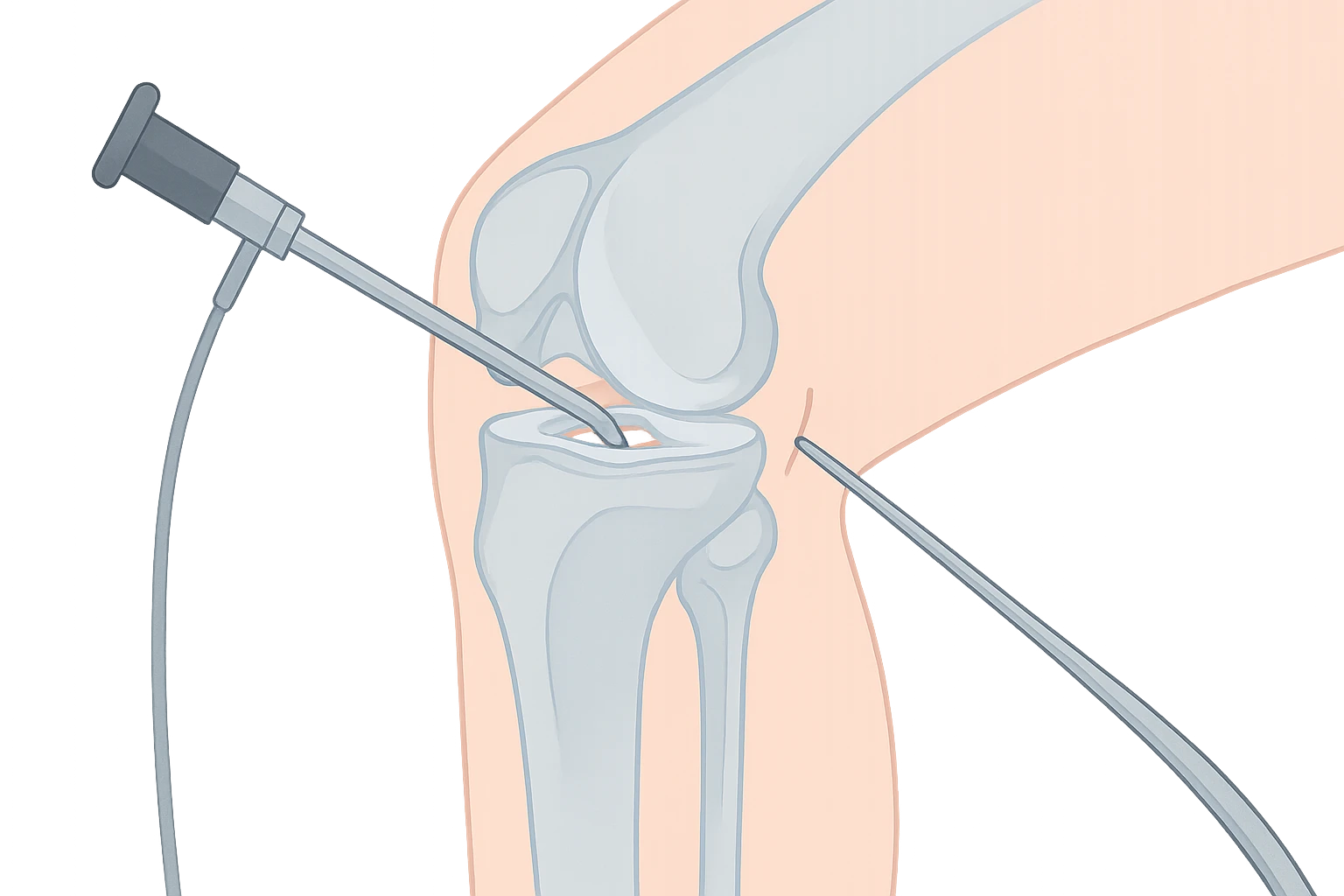

Knee arthroscopy has been one of the most commonly performed orthopaedic procedures for decades. Using a small camera and specialised instruments, surgeons can examine and treat conditions inside the knee through tiny incisions.

However, in recent years, updated research and clinical guidelines have shifted the way we use this procedure. Where arthroscopy was once recommended for a wide range of knee issues, we now understand that it is best reserved for specific situations.

This article reviews the current guidelines, explains when arthroscopy is still a valid option, and outlines what patients should expect when considering this treatment.

Large, high-quality studies published in journals such as the New England Journal of Medicine and the BMJ have shown that, for many people with degenerative knee conditions — including osteoarthritis and age-related meniscus tears — arthroscopy provides no long-term advantage over non-surgical treatments like physiotherapy, exercise programs, and weight management.

Cochrane Reviews and national guidelines, including those from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), recommend against arthroscopy for people with clear signs of osteoarthritis or degenerative meniscus tears without mechanical locking. This shift is based on evidence that:

While arthroscopy is no longer recommended for many degenerative conditions, there are clear situations where it remains beneficial:

A. Mechanical Symptoms

If a patient experiences true mechanical locking or catching (where the knee physically cannot move through its full range), arthroscopy can be used to remove loose cartilage fragments or repair torn tissue.

B. Traumatic Meniscus Tears

Younger, active individuals who sustain a clear injury to the knee — such as during sport — may benefit from arthroscopy to either repair or remove the damaged portion of the meniscus, especially if symptoms do not settle with rest and rehabilitation.

C. Loose Bodies in the Joint

Occasionally, bone or cartilage fragments float freely within the knee, causing pain and catching. Arthroscopy allows precise removal.

D. Certain Ligament and Cartilage Procedures

In selected cases, arthroscopy is used as part of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, cartilage repair procedures, or evaluation of unexplained joint symptoms.

Current best practice is to try non-surgical treatment before considering arthroscopy unless there’s an urgent reason for surgery. These options may include:

For many people, a structured non-surgical program can deliver equal — or even better — results than arthroscopy, without the downtime and surgical risks.

Arthroscopy can be highly effective in the right setting. Good candidates often share certain features:

The procedure is less likely to help when knee pain is due primarily to widespread arthritis, muscle weakness, or referred pain from other areas such as the hip or spine.

Knee arthroscopy is performed under anaesthesia, either general or spinal. Small incisions (about 5mm) are made around the knee to insert a camera and surgical instruments. The surgeon can then:

Recovery varies but most patients are walking the same day and return to office work within a week or two. Return to sport may take several weeks to months, depending on the procedure.

“Knee arthroscopy is no longer the ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution it used to be. In my practice, I focus on using it where the evidence supports clear benefit — particularly for mechanical symptoms and traumatic injuries.

For degenerative conditions, I work closely with patients to maximise non-surgical options first. This ensures we’re not exposing them to unnecessary surgical risk, and that if we do operate, it’s for a problem that surgery can genuinely fix.”

Future developments in arthroscopy — such as improved imaging guidance, regenerative cartilage techniques, and biologic therapies — may expand its role again. But for now, its most important contribution is in carefully selected cases, not as a routine treatment for knee pain.

Knee arthroscopy remains an important tool, but its use has narrowed. For degenerative conditions like osteoarthritis and age-related meniscus tears, current guidelines recommend against it in most cases. However, for patients with mechanical symptoms, traumatic injuries, or loose bodies, arthroscopy can still be highly effective.

The key is careful patient selection, a strong emphasis on non-surgical treatment first, and a clear discussion between surgeon and patient about likely outcomes.

1. What is the recovery time after knee arthroscopy?

Most patients can walk the same day, return to office-based work within 1–2 weeks, and resume light exercise after 3–4 weeks. Return to full sport may take 6–12 weeks depending on the procedure and your rehabilitation progress.

2. Is knee arthroscopy painful?

Some discomfort is expected in the first few days after surgery. This is usually well managed with oral pain relief, ice therapy, and activity modification. Discomfort typically improves rapidly within the first week.

3. Can knee arthroscopy cure arthritis?

No. Arthroscopy does not reverse or cure osteoarthritis. It can remove loose fragments or smooth rough cartilage surfaces, but it cannot restore the lost cartilage typical of arthritis.

4. What are the risks of knee arthroscopy?

While complications are rare, potential risks include infection, blood clots, nerve or vessel injury, stiffness, and ongoing pain. Your surgeon will discuss your specific risk profile before surgery.

5. How do I know if I need knee arthroscopy?

You may be a candidate if you have persistent mechanical symptoms (such as locking or catching), a confirmed traumatic meniscus tear, or loose bodies in the joint — particularly if non-surgical treatment has failed.

6. What alternatives are there to arthroscopy?

Physiotherapy, exercise programs, weight management, bracing, and anti-inflammatory medication are often effective alternatives. For degenerative knee disease, these are generally preferred before surgery.

7. Will I need physiotherapy after surgery?

Yes. Physiotherapy helps restore movement, reduce swelling, strengthen muscles, and speed recovery. It is a key part of achieving the best long-term results after arthroscopy.