Shoulder pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal complaints among adults, especially for those who work with their hands, lift weights, or perform repetitive overhead tasks. Two conditions often mistaken for one another are shoulder impingement and a rotator cuff tear. While they share overlapping symptoms, understanding the differences can help you know when to rest, when to seek treatment, and what kind of recovery to expect.

This article breaks down the distinctions in symptoms, clinical tests, imaging, and treatment pathways, helping you make more informed decisions about your shoulder health.

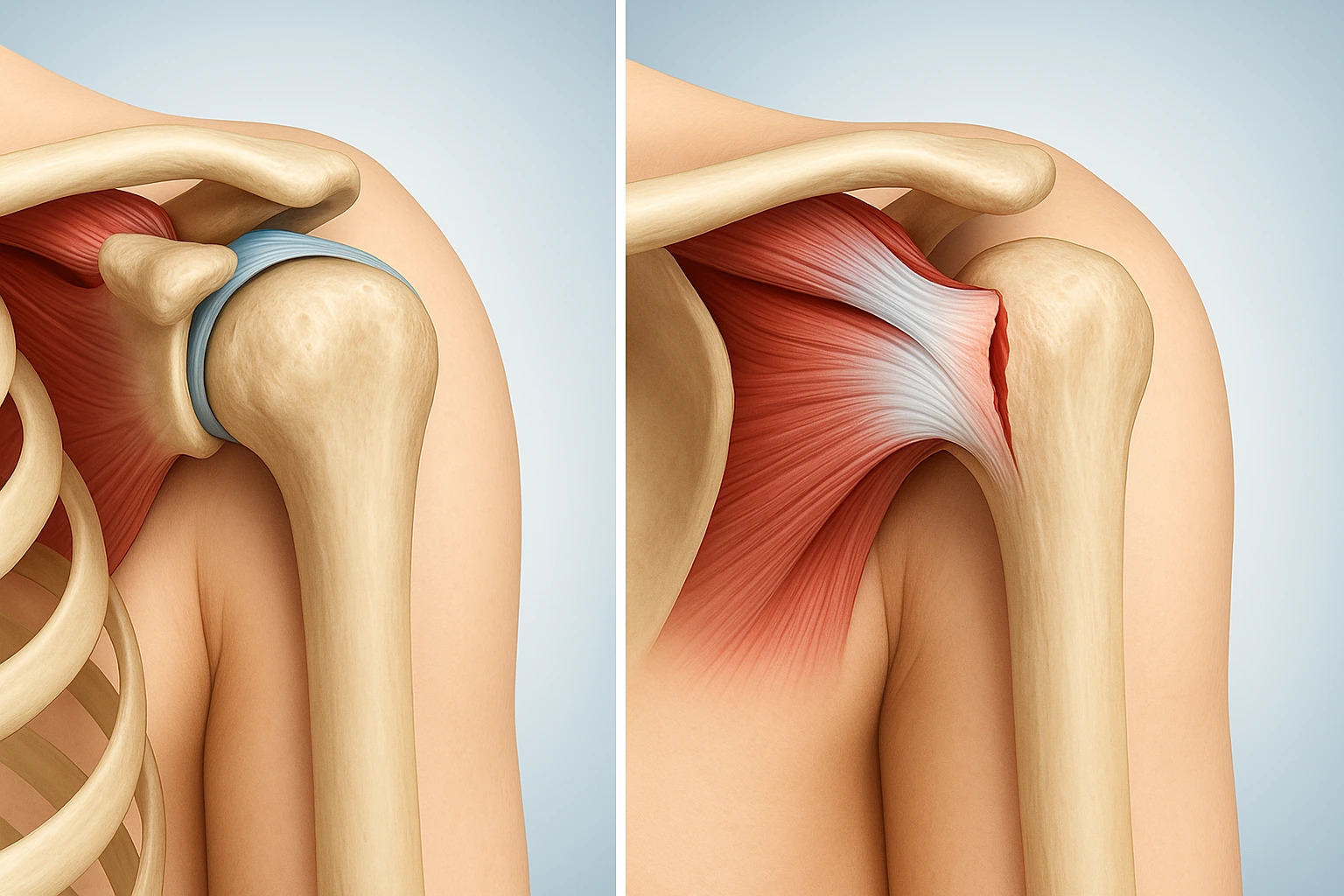

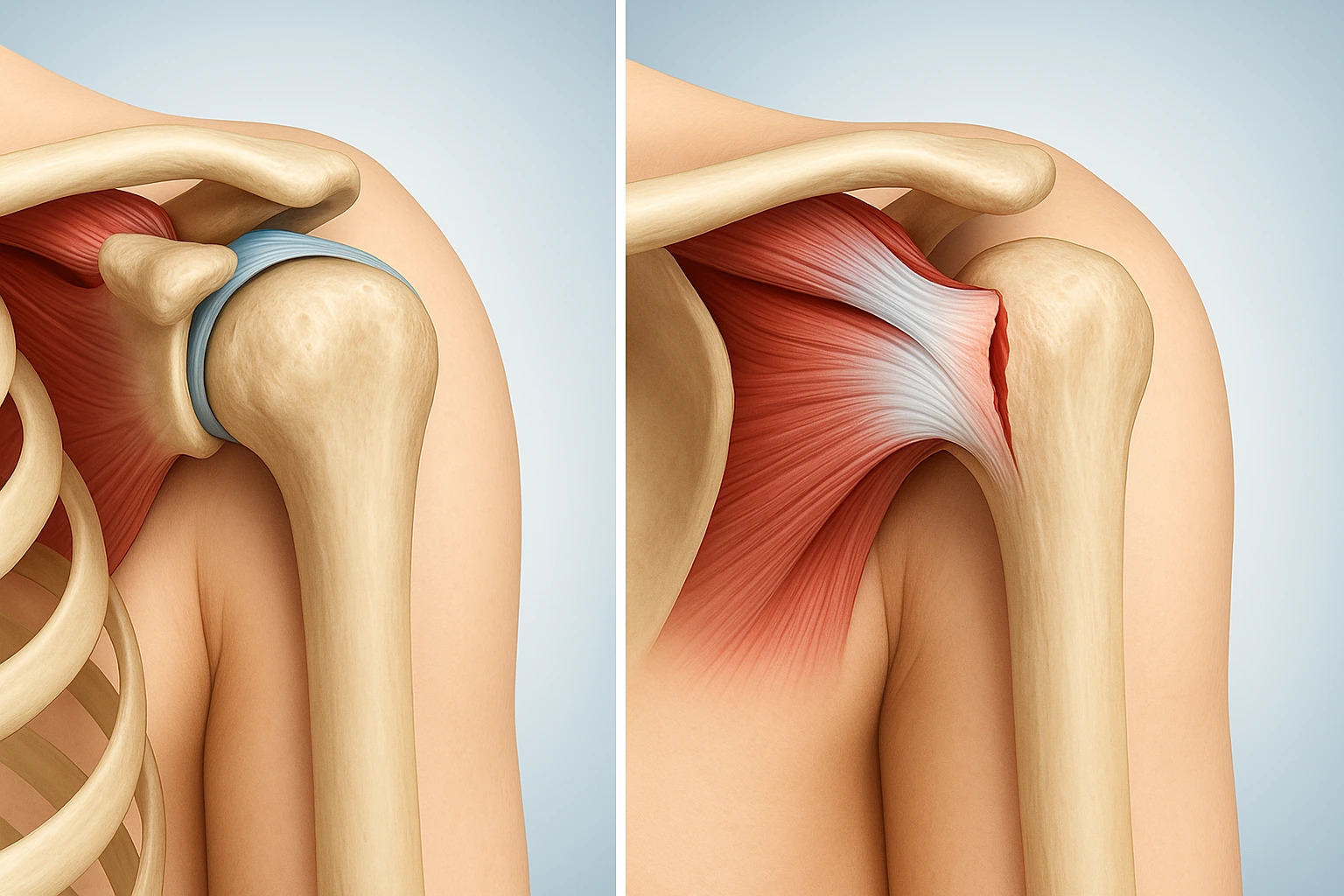

Shoulder impingement happens when the tendons of the rotator cuff or the bursa (a fluid-filled sac) become compressed or irritated within the narrow space beneath the acromion. This friction causes inflammation, pain, and limited mobility.

Impingement is typically the result of:

A rotator cuff tear occurs when one or more of the rotator cuff tendons partially or fully detach from the bone. Tears can be degenerative, developing slowly over years, or acute, caused by trauma such as a fall or lifting something heavy.

Common causes include:

Although both conditions cause shoulder pain, their symptoms have distinct patterns.

Shoulder Impingement:

Rotator Cuff Tear:

Impingement:

Weakness usually comes from pain—not actual damage. Once the pain eases, strength often returns.

Tear:

Weakness is noticeable and persistent. Even with pain relief, the arm may struggle with simple movements such as lifting a cup or combing hair.

Impingement:

Overhead movements, reaching behind the back, or lifting aggravate symptoms.

Tear:

Pain and weakness can occur during daily tasks, even those below shoulder level.

Healthcare professionals rely on physical tests to narrow down the likely diagnosis.

Practitioners often use several pain-provocation tests:

Positive results typically point to irritation of the rotator cuff tendons or bursa.

Tests focus on functional strength and tendon integrity:

When strength is significantly reduced—even with minimal pain— a tear becomes more likely.

While many shoulder issues can be managed without imaging, certain cases require a deeper look.

Imaging is usually recommended if symptoms persist beyond several weeks or if a significant traumatic event occurred.

=====

Because impingement and tears differ in severity and structure, treatment approaches vary.

Most cases improve with conservative, non-surgical care.

Focuses on:

With proper rehab, many people recover within 6–12 weeks, although long-standing cases may take longer.

Management depends on whether the tear is partial or full-thickness.

Surgery may be recommended when:

Recovery from surgical repair can take several months and typically includes structured physiotherapy.

Yes. Long-term untreated impingement can contribute to tendon degeneration, making the rotator cuff more vulnerable to tearing over time.

Seek professional evaluation if you experience sudden weakness, severe pain after trauma, or persistent symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks.

No. Many diagnoses can be made clinically. MRI is generally reserved for suspected tears, traumatic injuries, or symptoms that do not improve with treatment.

Partial tears may improve with strengthening and rehabilitation. Full-thickness tears generally do not heal without surgical repair.

Yes—low-pain, modified movement is usually safe. Avoid painful overhead activities and focus on posture and controlled shoulder strengthening.

Not necessarily. Many partial tears respond well to physiotherapy. Surgery is typically reserved for large tears, young active individuals, or cases unresponsive to conservative care.

Impingement recovery can take 6–12 weeks. After rotator cuff surgery, full recovery often requires 4–6 months of rehabilitation.